How can we evaluate our training?

Evaluating training sessions and each practice activity from a skill perspective can be difficult. Understanding the difference between learning and performance is a great first step to establish what are temporary and what are permanent changes in skill and behaviour.

Learning versus performance: Performance reflects short-term changes in behaviour, whilst learning involves relatively permanent behaviour change and leads to better transfer to competition, and is characterised by adaptability, persistence, automaticity and robustness under pressure

Role of errors: Errors - their size and variability - act as a signal of learning within practice. High performance outcomes often show fewer errors and support confidence and skill maintenance but typically transfer less to competition

Balancing confidence and competence: The confidence-competence continuum helps coaches and practitioners intentionally balance low-error, high-confidence with higher-error, learning focused practice by monitoring and planning error exposure across training

Estimated reading time: ~12 minutes

Performance and Learning

The primary goal of practice is to facilitate transfer to competitive contexts. Here, we must understand the difference between learning and performance as it relates to transfer.

Performance: temporary and mostly immediate changes in behaviour

- The effects are easily observed

- The outcomes are easily achieved by performers and happen quickly

Learning: relatively permanent and durable change in behaviour

- The effects are difficult to observe

- The outcomes are difficult to achieve and happen over longer timeframes

Activities which focus on learning are typically those that look more similar to competition performance and consequently, have higher levels of transfer. The concept of transfer and how much can be achieved in training is difficult in high-performance sport. This is because a blend of physical, technical, tactical and psychological elements of performance is required. For example, a practice activity that focuses on high levels of execution of passing to a moving target typically wouldn’t have much opposition pressure. This removes some information that players would typically use in-game to make a decision e.g. opposition players that may be close to the passing target influence if you do indeed pass to that player, how you pass to them, the speed of the pass, if you need to step and change direction etc. Consequently, we may sacrifice the level of technical and/or tactical similarity of practice to competition by focusing on higher passing percentage outcomes to focus on skill maintenance and enhance the level of confidence of the players.

Nonetheless, if we consistently incorporate practice activities that do not have a sufficient level of challenge and a focus on learning and subsequent transfer, we risk undermining the development of players and teams’ capacity to perform in competition environments. This is because players and teams’ performance during training can be misleading and an unreliable indicator of post-training/future performance (Ghodsian et al., 1997). As coaches and practitioners, we may erroneously think training has been effective as consolidating some skills or behaviours, when it hasn’t.

For example, imagine a training session that looks and feels awesome. The players have great energy because there are minimal errors through each practice activity. This level of energy and errors are repeated over 2-3 weeks. Because similar activities are performed, players are performing well due to the consistent repetition and exposure to similar contexts and environments over the period. Here, the problem is that fast gains in practice may give the impression that learning is taking place, even though faster acquisition is not necessarily beneficial for longer term learning (Farrow et al., 2008; Hodges & Lohse, 2022).

Hence, as practitioners and coaches, we must be aware of what learning is and how we can best design our practice to reflect game demands whilst holistically challenging and developing the players and team.

The goal of this article is to outline what learning is and its specific characteristics. Relatedly, I will briefly discuss the importance of errors (I will be writing on this specific topic in more detail in a later article) and how these relate to something called the confidence-competence continuum. I will be incorporating examples from Australian football. Importantly, this information must be considered in relevance to the goals and intentions of the coaching group and practitioners.

Nature of Learning

The table below explains the characteristics of learning and how they relate to learning.

| Characteristics of Learning | Inferring learning in practice over time | Examples in Australian Football |

|---|---|---|

| Adaptability | Skilled output across different conditions | The player can contribute strongly in tightly congested practice, expansive drills, stoppage, 1 on 1s etc. |

| Persistent over time | Retention of behaviour/skill is superior | Performing a handball drill and repositioning to receive the ball from teammate is consistent across 4v3 and 6v5 drills, then they can perform this repositioning and receiving passes in larger scale drills |

| Automaticity | Can identify, anticipate and perform multiple tasks at once and are more efficient with movements and behaviours | A player can communicate with teammates at a stoppage whilst pushing their opposition player under and engaging in scramble phase of play |

| Robust under stress | Consistent and durable behaviours and movements that are not affected by stress (pressure, high emotion, extreme heat) | The player performs well during practice activities that have high pressure and consequences (e.g. losing team is deducted points) |

Whilst we may all be interested in encouraging and optimising learning, the coaching group and players/team must be prepared to sacrifice some elements of performance during practice in order to maximise learning (Hodges et al., 2022). Additionally, the increased focus on learning can make the environment look more chaotic and messy. This is where errors and monitoring them comes in handy.

The role of errors and indicators of learning

To the contrary, inducing errors during training can be highly beneficial for learning. People do learn from their mistakes. In fact, one could argue that new learning only occurs after errors demonstrate the need for change.

Ghodsian, Bjork & Benjamin, 1997

We have established that increasing the difficulty of practice is normally achieved through an increase in the information in the drill, e.g. number of defenders goes from 5 to 8. This increase in information increases cognitive demands and challenge within the drill, which have been associated with enhanced skill retention, learning and transfer to competition. Nonetheless, the increase in difficulty performing the drill results in a decrease in performance, especially in beginners or if the drill is new for experienced players. This may be observed in higher errors or lower accuracy, slower decisions or more variable movements. Here however, errors provide the stimulus for reassessment and discovery.

Relatedly, there is a great recent video on Instagram on this by head coach of Richmond Footy Club, Adam Yze.

Note: Click on the image to watch the video.

He says ‘fail that way, fail going as fucking fast as you can to put yourself under pressure’. He encourages failures and errors as a way to get better. Acknowledging this approach with the playing group is important as it maintains motivation and the focus on development in a safe environment.

Continuing, these observations and errors are measurable and are learning signals that can be monitored to assess a few things such as:

- The stability or variability in error metrics over time, across specific drills or categories of practice activities (e.g. transition-based or match simulation)

- The magnitude and frequency of errors (you could allocate a value to different errors or how they are committed)

- How the magnitude and variability of errors changes based on specific manipulations made by the coaches and practitioners (e.g. an increase in defenders leads to more errors when players attempt kick a 45 degree kick into the corridor)

- How specific manipulations to the training drill may affect younger players performance and errors committed compared to more experienced players

- Changes in physical work rates and ‘efficiency’ of movements based on errors

This is not an exhaustive list. Additionally, these things can be compared relatively (e.g. per minute) across different practice sessions and competitive matches. Coaches and practitioners can also reinforce competence and autonomy through data and explanation of behaviour change across training (e.g. communicating a reduction of error rates and types of errors over time).

For example, let’s say we increase the field width in a particular activity focusing on attacking ball movement and faster transition speed. This hopefully leads to more open spaces in the middle of the field and subsequently, ‘riskier’ passing decisions and passing actions towards those spaces. This may increase the passing efficiency of the team considering there is more space. But we may then want to increase the defensive pressure so add a +1 on the defensive team, likely leading to a lower passing efficiency and more turnovers. If we monitor the passing efficiency in addition to the types of passing errors, the turnovers made and their respective locations, we can assess these questions above and begin to understand patterns of behaviour and levels of challenge in relation to manipulations we made as coaches and practitioners. Whilst an initial database must be built, we can understand longitudinal patterns over greater timelines and even benchmark and create indexes for specific activities commonly performed at in training.

Nonetheless, let’s say that the errors are too large or too frequent and the coach wishes to intervene. We can use a bandwidth approach to providing feedback on the errors, where a threshold of acceptable errors is implemented, and anything over this amount is where a coach intervenes. This isn’t the place to extend on this topic, but I will write an article in the future focusing on augmented feedback approaches and strategies. If you are interested in reading more about the bandwidth approach right now, see this article: Read article here

What about confidence during training?

A higher focus on systematically designing practice to ‘incorporate’ errors during practice can have beneficial effects for learning and skill transfer to competition. However, we must acknowledge the benefits performance style training can have on performance, with the main outcome being confidence and motivation (in players and coaches). Thus, we must be able to incorporate and manage errors in a way that can balance this with maintaining confidence at an individual and team level. This is where the intentional acknowledgment and implementation of the competence-confidence continuum is helpful.

The confidence-competence continuum

This continuum has confidence on one side, and competence on the other. Each element of the continuum is described as:

Confidence training: reinforce skills and strengths, motivate and instil encouragement and develop a level of automaticity

- Perform and implement when you want the players and team to feel ready and confident

- Lower levels of information present in the activities

- Minimal errors

- Looks neat and clean

- E.g. captains run

Competence training: higher levels of similarity to competition and consequently, have higher levels of transfer to competitive environments and higher levels of learning

- Perform when the there is a capacity to have more errors in training

- More information and complexity in the activities

- Higher level of errors

- Looks messy and chaotic

- E.g. match simulation

For a detailed explanation of the confidence-competence continuum, Job Fransen has an article explaining it’s relation to coaching in Rugby. Read article here

Using the above information, we can design practice in a way that leverages variability (here, variability is when several variations of a skill or behaviour are implemented or observed) to achieve both confidence and competence focuses within one practice activity or within one session. Below is an example in-season training week, where we have 1 week between each competition game.

| Monday | Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Review previous game + Recover | Training + review | REST | Training + Preview upcoming team | Captains Run | Game | Rest |

Tuesday’s session may look something like this:

| Activity/drill | Goals | Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Skill circuit: handball, straight line kicking, overhead marks, walking handball game | Skill maintenance with minimal or predictable variability. Walking handball game relates and builds into next drill to be performed (i.e. gauntlet) | Within each station of the circuit, organise each execution of the reps so it is like ABCABCABC. That is, the handball station may be left hand handball, righthand handball then a moving target handball |

| Handball gauntlet to entry and exit (player numbers in congestion may be 5v3, 7v5) | Unpredictable but increase in information leads to higher challenge and difficulty, but maintaining a relatively higher level of success in each drill repetition (remember high success = higher confidence) | Serial skill repetition as above but with more variability. Here, we can manipulate the player numbers in the gauntlet to give the offensive team more numbers, leading to successful passing outcomes. We could also increase the width of the gauntlet so there is more space to be used by the attackers. It is a lower challenge level but still more dynamic and unpredictable |

| Scramble into forward half press | Drill focusing on something needing improvement from previous week game: Handball transition and defensive positioning going into forward half | Scramble phase at the start of the drill is game-like – unpredictable and random. This focuses on specificity and transfer to game situations. It should also build on the previous handball drills performed in the session. Defensive positioning and off-ball movements requires higher attentional demands from each player and the team. The drill would continue into the next phase (i.e. opposition team kicks out and attacking team is now forming a forward half defensive press) where the efficacy of the forward press can be observed and the information players use to make defensive decisions is game-like. |

| Goal kicking | Skill execution and confidence but with minimal repetitions (can stress importance of execution if desired) | Change the position of set shots but perform 2-3 at each position, so there is minimal variability. This could also be manipulated so the position does not change. |

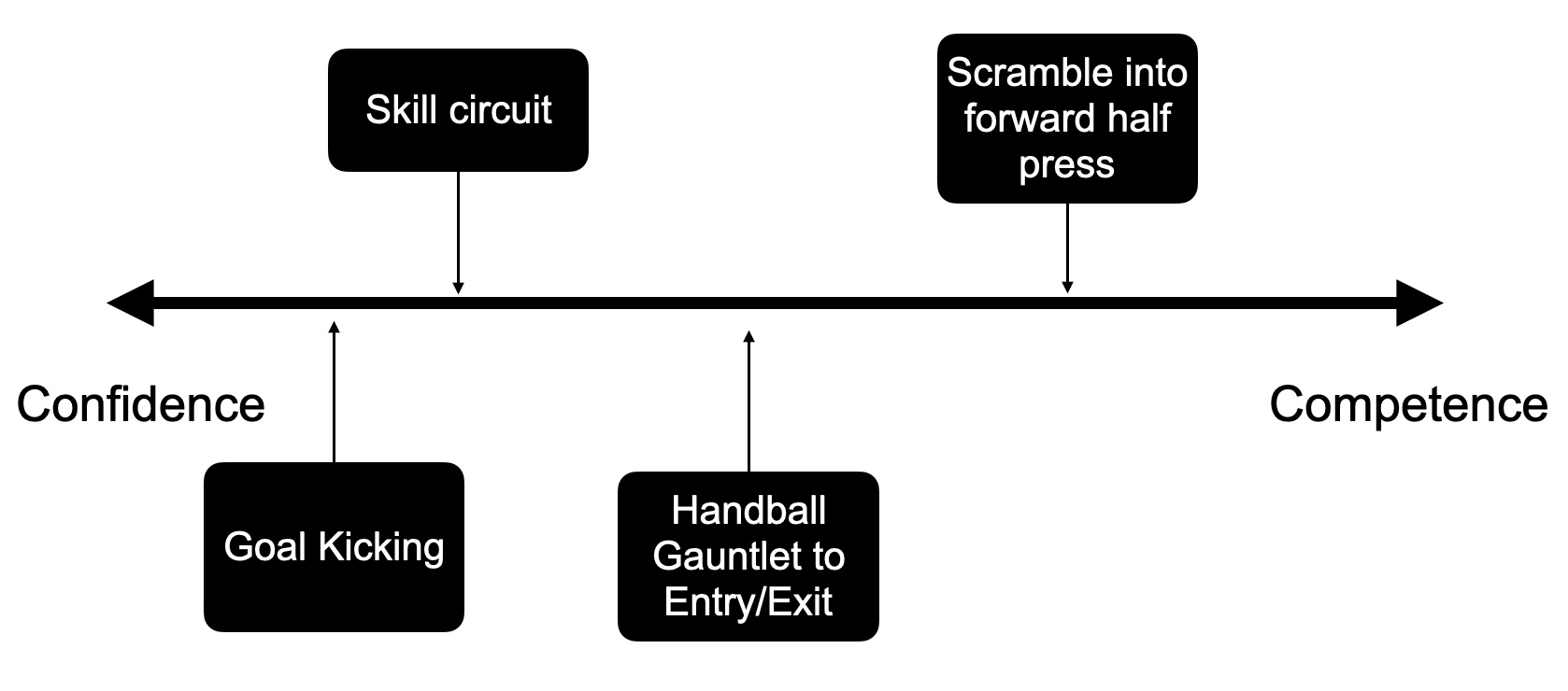

So, within this session we have a mix of higher repetition of skills for our performance/confidence focus in the skill circuit and handball gauntlet, followed by a more unpredictable and challenging/competence activity focusing on learning in the scramble to forward half press, finished by a relatively repetitive goal kicking activity. This last activity can be manipulated to make it easier if a higher level of confidence is desired. It could be athlete led too, where they’ll likely perform a highly repetitive drill. This is visually reflected on the confidence-competence continuum below (Figure 1).

Thursday’s session (main training session of the week)

| Activity/drill | Goals | Variability |

|---|---|---|

| Skill circuit (similar to above) | Repetition, motivating and confidence building | Minimal variability, skills are repeated with no or minimal unpredictability and challenge |

| Match simulation: 18v18 | Matchplay intensity: the speed, structure, defensive pressure and time constraints are as like matches as possible. Consequences are also present, e.g. turnovers are played out where possible and scores are kept | Skill executions are completely random based on the game situation, enhancing the transfer and specificity to match-play. Important to note is that this reduces the number of repetitions that a player accrues in this drill |

| Lines (challenging) | Positional group focuses. Midfield group may focus on stoppages into scramble play. Forwards and defenders may focus on leading patterns and defending them | Higher intensity and similarity to match-play. Consequently, there is a higher level of unpredictability and errors |

| Lines (repetition and quality) | Positional group focuses. Repetitive activities that focus on line specific skill. For example, midfielders may perform 1v1 body work and positioning | There may be a reduction in the velocity and unpredictability of the drill, so there is minimal/lower level of errors. The focus here is more on confidence and skill maintenance |

| Individual skills | Up to the individual player | Likely going to be minimal variability to increase confidence and enhance motivation going into the upcoming match |

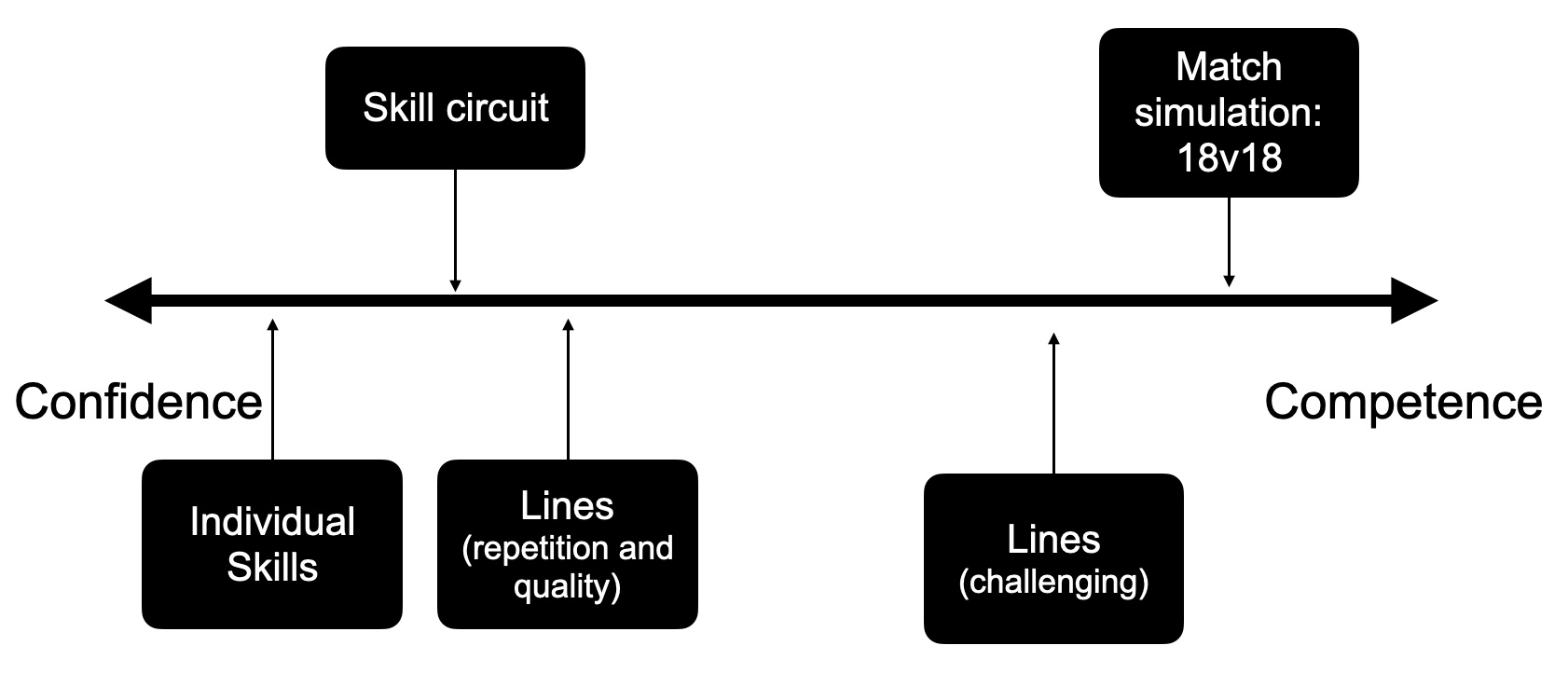

This session begins with a repetitive, performance/confidence focused activity with the skill circuit. We then have our most similar activity to competitive performance, with high amounts of unpredictability and complexity in match simulation. Skill executions and movements are random based on teammates and opposition positioning, where the ball is etc. The lines (challenging) entails a more dynamic but important part of each positional groups role and can be fast-paced, dynamic and challenging, hence, more competence-based. We would expect errors to be higher here, so learning is higher. Conversely, the Lines (repetition and quality) would remove key informational sources and should have a decrease in intensity and velocity of movements and executions. So, errors would be significantly lower resulting in higher performance and higher confidence. This is especially important finishing the session. Lastly, individual skills can be highly repetitive and only include 1-2 key skills such as short range kicks, overhead marks or groundballs. This is visually reflected on the confidence-competence continuum below (Figure 2).

Some (extensive) points to consider

- Higher specificity almost always leads to lower exposure and repetition of skills and behaviours E.g. the handball component of skill circuit performed each session may have a player perform 15 handballs for example, but they are not game like. Whereas the match simulation will have a player perform 2-4 handballs but with all the relevant information that they will use in a competitive match such as opposition player pressure, the position of their teammates, the position on the field etc.

- Higher error rates are a good indicator of challenge and subsequently, learning. Here, use a ‘Goldilocks’ approach with error manipulation and implementation.

- Too many errors = demotivating and likely too complex for the players/team

- Too little = not stimulating or challenging enough to evoke learning and adaptation

- The idea is to have an amount of errors that keep the players and team motivated to improve on them

- Information and decision-making processes likely facilitate transfer to competition more than the similarity of movements alone. However, it is information and action together that produce superior transfer

- There may be transfer to competition, but it may not be super specific if the relevant information is not present in the drill. For example, a handball may transfer to competition but the higher skill a player has means that the information players use in a competition match must be present during training so that the skill can transfer. Information such as opposition pressure, position on the field (defensive 50 vs forward 50), their teammates positioning etc. are all relevant information sources players use to decide on who to handball to and at what moment.

- For higher level athletes, creating new information to promote learning is necessary and could be integrated by introducing more variability or by a coach elaborating on current information e.g. give new feedback or another task to focus on during performance (Hodges et al., 2022). This could even be achieved through video feedback and increased information presented to the player and/or team.

- For drills with higher errors, coaches can promote competence by using praise on the good attempts/reps in the activity rather than giving feedback on the bad attempts

- The mindset of this approach must be based on hard work and growth, where individuals believe that improvements come through hard work and persistence through exposure to challenge

Conclusion

A key outcome for coaches and practitioners should be recognising and understanding the difference between performance and learning. Practice that focuses on performance has greater effect on short term performance but neglects longer term learning and transfer to competition. Here, the intention of each drill must be known and explicit, where coaches knowingly implement a focal point based on learning or performance based outcomes. Within each focus, errors can be used as a signal to monitor the level of learning based on the described characteristics.

References

Ghodsian, D., Bjork, R.A. & Benjamin, A.S. (1997), Evaluating training during training: Obstacles and opportunities, Training for 21st Century Technology: Applications of Psychological Research, pp. 63-88, Washington, DC: American Psychological Asociation.

Hodges, N.J. & Lohse, K.R. (2022), An extended challenge-based framework for practice design in sports coaching, Journal of Sports Sciences, 10.1080/02640414.2021.2015917.

Farrow, D., Pyne, D. & Gabbett, T. (2008), Skill and Physiological Demands of Open and Closed Training Drills in Australian Football, International Journal of Sports Science and Coaching, 3(4), 485-495.

Fransen, J. (2024), URL: https://www.rugbycoachweekly.net/rugby-coaching/when-performing-doesnt-mean-learning?srsltid=AfmBOoqilgcchX0DAS_wHseooY8SUK_ci-5dE8VTvB6nqg9pCbrNeqLx, date: 24/11/2025.

▲ Back to top