We don’t talk about errors

Using errors as a guide and part of a decision-making framework on training design is difficult but can be very powerful to stimulate learning. When used in conjunction with the constraints-led approach and the challenge point framework, we optimise our evaluation processes.

- Integrating the challenge point framework and the constraints-led approach: These frameworks provide a robust way to evaluate player and team learning in training and can be done so as a periodic measure of learning

- Measure and monitor the level of challenge in practice through the constraints-led approach: Monitor the constraints manipulations made in training, the number and type of errors and how the players subjectively rate the challenge of the drill

- Using this system can help evaluate the effectiveness of our training: This approach can complement the coaches subjective experience and evaluations whilst further mitigating potential implications including team selection, team values and standards and player confidence

Estimated reading time: ~10 minutes

In fact, constructing the conditions of training so as to avoid or minimize errors may simply defer those errors to a time and place where they matter much more.

R.A. Bjork, 1994.

Initial Problem

As I have discussed in a previous blog post here, performance during training is often an unreliable indicator of post-training performance. Manipulations that enhance performance during training can yield poorer long-term performance compared to manipulations that degrade performance during training, especially in performance contexts (i.e. competitive matches). This is why I have mentioned the quote above by Robert Bjork, where if we do not construct training conditions that have some difficulty and result in errors, these errors may be ‘deferred’ to competition contexts.

Consequently, we should try to integrate a system to monitor practice and assist decision-making of practice design. Such a system to guide decision-making can use a blend of the following frameworks, The Challenge Point Framework and the Constraints-led Approach.

Challenge Point Framework

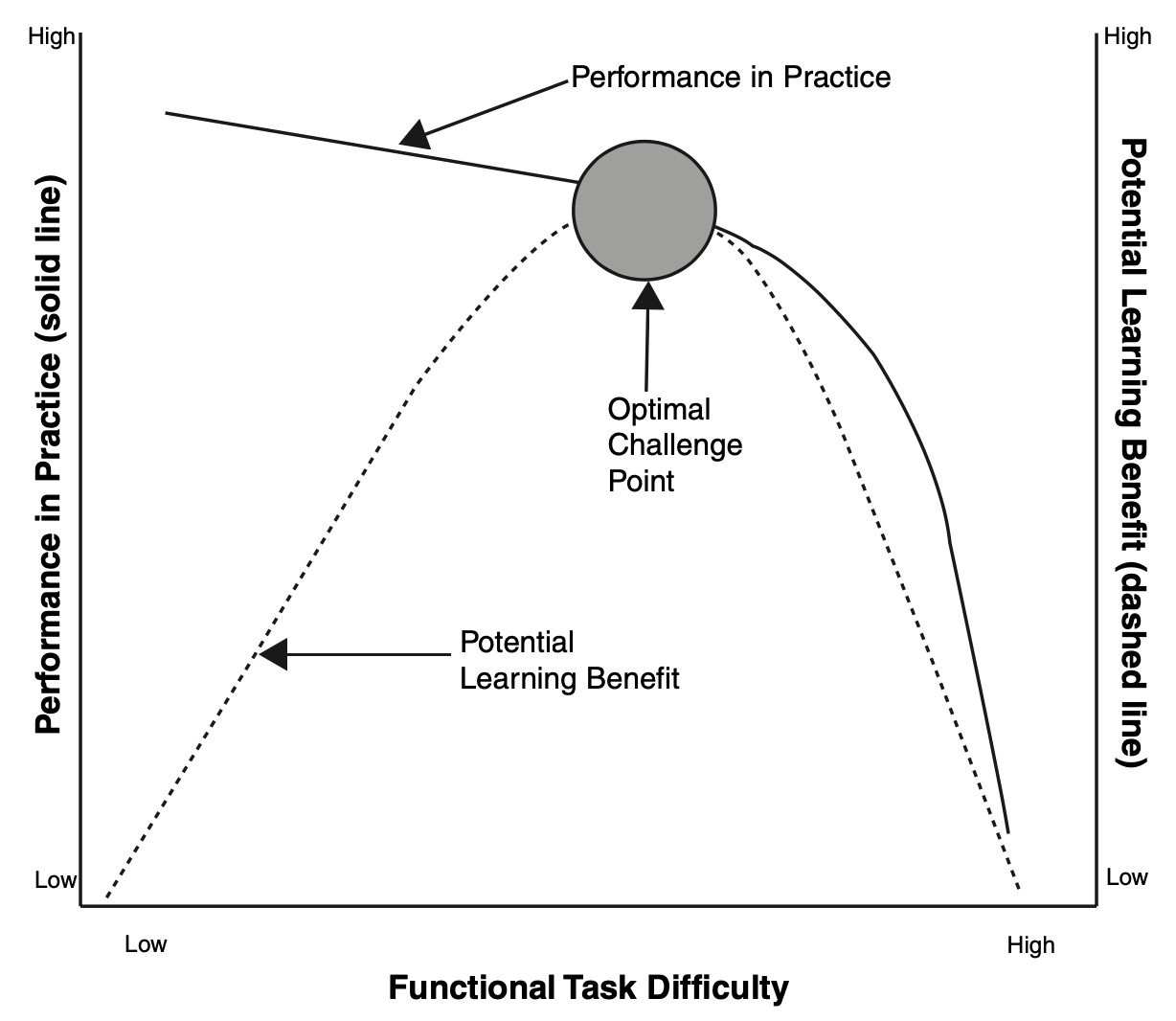

The Challenge Point Framework (CPF) describes how the interaction between task difficulty and performer ability influences the potential for learning (Guadagnoli & Lee, 2004; Figure 1). Accordingly, there are ‘optimal’ conditions to design practice. These optimal conditions vary according to the player. Here, learning occurs by manipulating the level of challenge according to the skill level of the player(s).

In line with this theory, learning occurs by increasing the challenge, which is normally achieved by increasing the amount of relevant information into the practice drill. The level of information mustn’t be too much so that it is too complex for the learner(s) but it also mustn’t be too easy and not stimulating enough. Hence, the optimal challenge point. You can think of it like Goldilocks (i.e. we want something in the middle). Learning is meant to be most accelerated when the practice conditions are manipulated based on the learners skill level and the difficulty of the task. And two simple things we can use to measure the level of challenge in our practice is errors and their size and variability and a subjective rating of challenge collected by each player. More on these later.

One way to manipulate and monitor the practice conditions we integrate into practice is through the aforementioned Constraints-led Approach (CLA).

The Constraints-led Approach

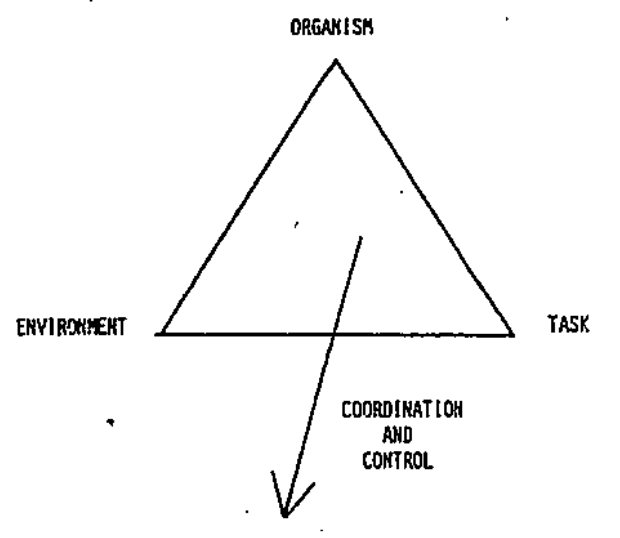

The CLA describes how skilled behaviour emerges through the interaction of three constraints: i) individual, ii) environmental and iii) task (Newell, 1986; Figure 2). This framework helps describe how skilled behaviour emerges through these constraints. In coaching, we mainly manipulate task constraints to influence the behaviour/movement of the players and team. These directly relate to the goal or objective of the drill.

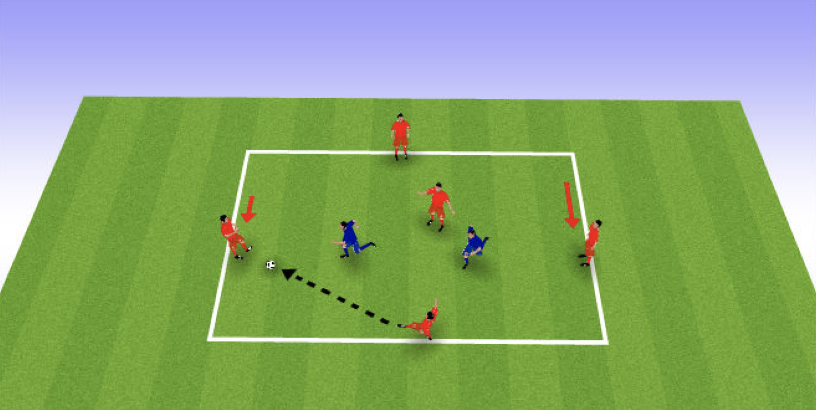

For example, we may set up a Rondo (Figure 3) to increase the amount of defensive pressure on the ball carrier and emphasise the re-positioning of those attackers without the ball. We can manipulate the space between the attackers, how many defenders there are, or the overall space used in the drill etc. These are task constraints that directly impact the objectives of the drill.

The interaction of these three constraints (i.e. individual, environment and task) determines what information is in the drill and subsequently affects how the players and team behave. For example, if we manipulate the task constraint of ‘space’ by increasing the distance between the attackers, we obviously give more space to the attackers. This then gives them more time and space to beat the opponents, so they re-position effectively, hit targets etc. Conversely, if we manipulate the drill so that there is less space, the defenders can more likely influence their opponents passing, they generate more pressure to then create turnovers. We measure these things and monitor how they change.

You get the idea.

We can monitor skilled behaviour better when we integrate the challenge point framework with the constraints-led approach.

Nonetheless, this requires a systematic and thoughtful approach to designing practice.

Integrating the CLA with the CPF

In 2011, Pinder and colleagues proposed “representative learning design”. This concept is central to what we try to achieve in sport, with the overall aim of practice being transferring the skills and behaviours to the competition environment. The idea is that higher representativeness looks and feels more similar to matches.

Integrating the CPF using the CLA aims to recognise the benefits of representative learning design and can assist to optimise the balance between physical preparation, and tactical and skill objectives. Through training manipulations we make, athletes should be able to increase their awareness and sensitivity to specific sources of information that they use to make decisions. For example, a subtle movement or identifying a specific leading pattern by a teammate to hit a kick.

Monitoring challenge using the constraints-led approach

We will approach this by using a more holistic measurement of the level of challenge that incorporates measures of errors and importantly, in a way that we can systematically monitor and manipulate training. This will be done to understand which drills are more difficult based on player perception and how this interacts with the constraints implemented in different drill types and how their skilled behaviour changes as a result. The method would be as follows:

- Collect data on training constraints, such as drill length, drill width, the number of players, time in the drill etc

- Collect and measure data on skill involvements, their frequency and proficiency levels such as handballs per minute, handball proficiency, kicks per minute, marks etc. Additionally, social network measures (see previous blog post describing what they are) should be included

- Collect a rating of perceived challenge from each player. This is a subjective measure from each player that is a 1-10 rating of how challenging they perceived the drill to be (Hendricks et al., 2018a, 2018b)

This approach combines objective and subjective data.

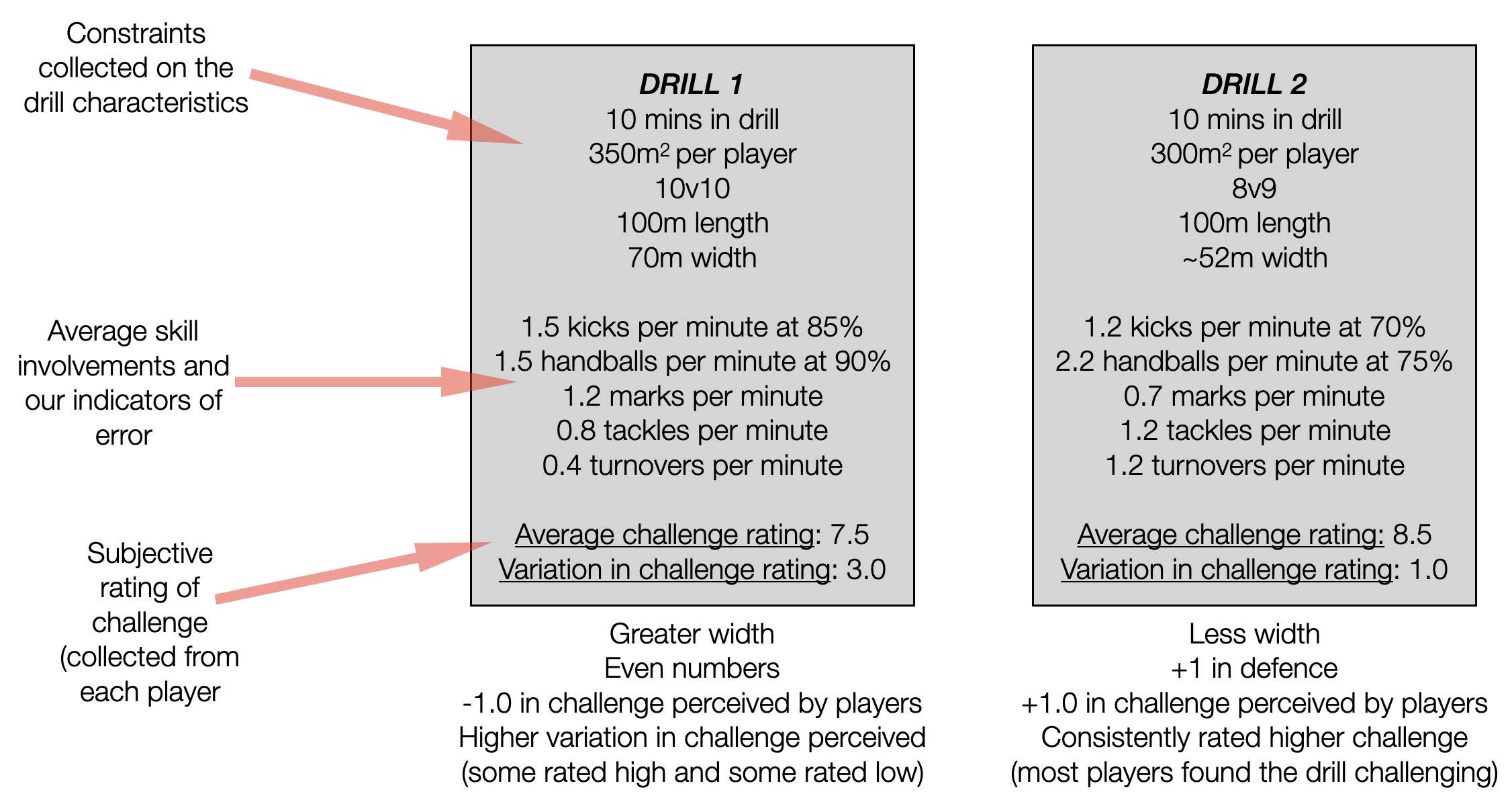

Consider the below figure showing some made up constraints and numbers between two drills.

We may take away from Figure 4 that the less width (it is relatively narrow, but this is stressing measurement more than anything) and +1 player in defence in DRILL 2 made it harder to move the ball for the attacking team. Resultantly, there were more tackles and turnovers and lower proficiency percentages for passing (i.e. attackers were not hitting targets). The subsequent increases in tackles and turnovers may have made the game more physically demanding (e.g. higher change of direction, accelerations), so DRILL 2 was perceived to be more difficult when considering all of these factors.

The level of challenge here is considered in relation to both the availability and usability of information in the form of the constraints we have incorporated and manipulated. And now we can systematically monitor it in addition to the objective (i.e. skill outputs and error indicators) and subjective (i.e. rating of perceived challenge) responses.

This system ensures a periodic measurement and monitoring of learning in a systematic way which helps to evaluate the effectiveness of our training.

Implications using the CLA to monitor the level of challenge

Using this approach to coach and teach our players, we can create tangible and testable questions. For example:

Do players find x drill more difficult than y drill? What might this be due to – increased width, an outnumber to the attacking team, a specific rule imposed by the coaching group etc

How does the players level of challenge change when we manipulate the number of defenders? Is there a relationship with their skill outputs?

Is there a specific time we should spend in a drill to achieve a specific level of challenge?

How does the level of challenge change according to the players level of experience? E.g. 1-4 year players vs 4+ years

When does a players performance ‘collapse’ under increasing challenge?

How does a player in rehab or individual skills training respond to changes in practice structures? E.g. if we change the order of a skills circuit to more random, do they find it more challenging and by how much?

I could go on and on. This list is not exhaustive.

Nonetheless, we must be mindful of some more implications that extend into the reality of team sport performance and the psychology of high-performance environments.

A more challenging training environment

Player/team confidence: This is a very important implication. Participants who study in blocked conditions which inherently have less challenge (i.e. more repetitive and predictable) report optimism in their future capability to perform the skill (the reverse pattern is also true; performing dynamic and variable skills leads to questioning future capability to perform skills)

Team/player selection: Whilst a player making a specific level of errors is healthy for learning, it may be perceived negatively by the coaching and selection committee, affecting their perception of the players ability. There is an applicable video of Carlton Footy Club and head coach Michael Voss mentioning the players who have been training well, saying “he trained very good”. Obviously however, we don’t know how Michael Voss assesses the players performance at training (See video here). Nonetheless, coaches keep receipts of training performance

Team standards and trademark: There is a mountain of anecdotal evidence in AFL where players want to be ‘clean’ as a standard and often it is a value or a ‘trademark’ they set for themselves. If training sessions are characterised by too much challenge leading to higher rates of error, players and/or teams may feel as though they aren’t living up to higher standards and instead, accepting mediocrity. See the AFL article on Lachie Neale where he says ‘do the basics well’. (Read article here).

A higher risk of player injury: If training is designed to elicit a higher level of challenge and learning, and subsequently, higher similarity to matchplay, there are medical and physical implications. Let’s consider an example. If matchplay is our most similar drill to competition, it has most components of what matchplay entails: increased tackling, increased change of direction, increased congestion and general physical contact and a higher level of information at higher speeds so inherently more complexity. All these factors together need to be acknowledged and understood from a risk management perspective (tackles can be managed by communicating to the players not to go all out, no run down tackles etc). For a specific example, see the below article where Sydney Swans captain Callum Mills “…was tackled in a contested drill and fell awkwardly…” subsequently injuring himself (Read article here).

A less challenging training environment

There are multiple attempts to practice and learn from a broken down scenario: a less challenging environment may be designed in a way where multiple repetitions of one practice drill are performed, giving the players and team more opportunities to practice. Whilst this isn’t truly match-like, this approach can consolidate a pattern of behaviour, movement or skill for a player/team

Impede perceptions of competence: a player or team that trains with less challenge (i.e. more predictability and repetitive training) may perceive that they possess a greater ability than what they actually do because of the artificially easy training conditions

Schedules that are preferred by learners/players typically produce the least learning: here, players may prefer training schedules that are more predictable and contain less errors and produce better performance in training

The quality of your training opposition and their skill level: as squads are limited by salary cap, desirability of being in the environment and playing there etc, there is obviously a limit to how much talent you have access to bring in and can have available at the club. So, there will always be 1st division players up against 2nd division players. This affects the quality of the training sessions

Nonetheless, these implications can be somewhat remedied if we ensure our monitoring system encapsulates what I have been discussing. For example, the coaches obviously keep receipts of training performances, but we can also do this objectively using this system. Pairing them both together can provide a more holistic appraisal of the players training performance and from a longitudinal perspective.

Conclusion

Integrating the challenge point framework and the constraints-led approach is a useful way to incorporate periodic measurements of learning in training. Use errors as a proxy of learning in addition to skill measurements and player evaluations of the perceived level of challenge to evaluate how these change in response to manipulations to constraints. This system should be used in conjunction with coaches’ expertise and experience to optimise preparation.

References

Pinder, R.A., Davids, K., Renshaw, I. & Araújo, D. (2011), Representative Learning Design and Functionality of Research and Practice in Sport, Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 33, 146-155.

Guadagnoli, M.A. & Lee, T.D. (2004), Challenge Point: A Framework for Conceptualizing the Effects of Various Practice Conditions in Motor Learning, Journal of Motor Behaviour, 36(2), 212-224.

Newell, K. M. (1986). Constraints on the development of coordination. In M. G. Wade & H. T. A. Whiting (Eds.), Motor development in children: Aspects of coordination and control (pp. 341–360). Martinus Nijho.

Hendricks, S., Till, K., Oliver, J.L., Johnston, R.D., Attwood, M.J., Brown, J.C., Drake, D., MacLeod, S., Mellalieu, S.D. & Jones, B. (2018a), Rating of perceived challenge as a measure of internal load for technical skill performance, British Journal of Sports Medicine. DOI: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099871.

Hendricks, S., Till, K., Oliver, J.L., Johnston, R.D., Attwood, M.J., Brown, J.C., Drake, D., MacLeod, S., Mellalieu, S.D., Treu, P. & Jones, B. (2018b), Technical Skill Training Framework and Skill Load Measurements for the Rugby Union Tackle, Strength and Conditioning Journal, 40(5), 44-59.

▲ Back to top